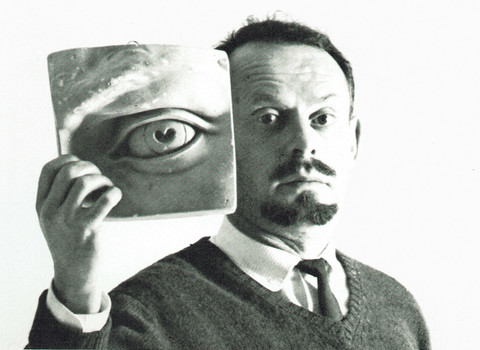

This text marked Frank Eidlitz’s posthumous induction in the AGDA Hall of Fame in 2006.

To say Frank Eidlitz was energetic is to damn him with faint praise. To say he was hyperactive is a serious understatement. To say he was manic is getting a little closer to the truth, but this excessive energy was never wasted, he managed to channel it all into his work, and during the sixties and seventies he produced some of the most dynamic graphic design seen in Australia before or since.

He arrived in Melbourne in 1955, from post-war Hungary and an education at the esteemed Royal Academy of Art, Budapest, alma mater of luminaries like Vasarely, Maholy-Nagy, Kepes and many others.

Somebody had told him that there were many opportunities for graphic designers in Australia, but he discovered that to be a slight exaggeration. He needn’t have worried.

After a couple of years at Atlas Publications, he landed what became the plummest job in Melbourne. For eight years he was an art director at USP Benson, a multinational advertising agency with the choicest accounts of the time.

It was a golden period for USP. Not only did they have Colin Uren on staff, a universally admired talent, the electric presence of Frank Eidlitz (or Eyelids as Bruce Petty preferred), but they had imported Les Mason from California. Halcyon days indeed.

They so valued Eidlitz that they encouraged him to be involved in outside projects. A relationship grew up between he and Alfred Heintz, a spectacular Public Relations entrepreneur. He became a kind of mentor for Frank, and he could swing the biggest jobs for the most important clients with Frank’s highly credentialed Europeanness. They formed Prestige Publications to handle major print projects for very major corporations, and they got swags of it.

Brian Sadgrove recalls seeing one of these productions very early in his career, for the merging of several huge mining companies called The Fabulous Hill, and being ‘blown away’ by the cover. This was in 1959.

More followed—for McPhersons, an engineering export firm who made nuts and bolts, Comalco the giant aluminium smelter, the Gas and Fuel Corporation of Victoria and others, all of them impressive, but by far the most impressive work he did, he did under the patronage of USP… it was his publicity campaign for the Shell Company in 1964.

The 24 sheet poster series he did for them in this period is some of the most powerful work done in the sixties — and remember the sixties in Melbourne was an explosion of design movements from all directions. The Englishness of Melbourne design represented by Jimmy James, Max Forbes and Dick Beck was being challenged by the Swiss School of typography exemplified by Heinz Grunwald, a Swiss, me, not a Swiss, and the young Brian Sadgrove. Frank brought his passion for the new Op Art, inspired by Hungarian artists like Vasarely and the Bauhaus experimenters, Les Mason, newly arrived, introduced West Coast American wit and sophistication and Arthur Leydin had established a tough nosed Chicago pragmatism.

It was a wild and exciting time for young designers. The Shell campaign made Eidlitz’s name. He was immersed in the pulsating, staccato, binary, ebullient, restless imagery of Op and Kinetic art and he used it freely in his designs, paintings and sculpture. It perfectly fitted his personality. Not only were the offices of USP Benson bedecked with his Vasarely inspired paintings, but those of the Shell headquarters as well, USP even sponsored an exhibition of his art at the Museum of Modern Art of Australia — John and Sunday Reed’s pre Heide showcase of outstanding Australian modernism.

When the Churchill Fellowship series was introduced in 1965 Frank was first in with a convincing case that he should have the inaugural Design and Communications award — and he got it.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology was his target, and Kepes at that time had just established the Centre for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) after having worked as head of the Light and Color Department of the Institute of Design in Chicago, then known as the New Bauhaus, since 1937. He joined MIT in 1946.

Some of us have had the opportunity to work under people for whom we have deep admiration. Eidlitz not only had that privilege, but the object of his admiration was also a genius. Kepes had the solid gold credentials for a master of the modern movement. With fellow Hungarian Maholy-Nagy he was a central part of the elite of the Bauhaus, and went to America with Nagy when the legendary school moved to Chicago. Kepes’ mates were Gropius, Buckminster-Fuller, Marcel Breuer, Charles Eames to name but a mind-blowing few.

When Eidlitz returned home, after a year in America in which he undertook commissions for American companies including the development of a new station identification symbol for network NBC, he found the going a little slow and worked from his home in Beaumaris, but it didn’t stay like that for long.

By the late sixties he was commuting between the two capitals, a week in Melbourne, a week in Sydney, important commissions in both places, and by 1968 Sydney won. He was soon travelling backwards and forwards to Europe and America for art showings. Harry Williamson recalls, ‘every time I met Frank he was going overseas somewhere’.

He had exhibitions in Melbourne, Sydney, Newcastle, Alice Springs, Queensland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, New York and West Berlin, often over and over, while still absorbing and expressing the extraordinary experiences he had had at MIT.

Experiments with early computer art, light and colour theories from the masters of the genre, with the constant mantra of the need to blend art with technology. Frank was a willing ambassador.

His was a stellar career in graphic design. Blue chip clients, indefatigable energy, and a gift, inspired in no small way by his early mentor, Alfred Heintz, for constant self promotion. At one stage he had a complete side wall of his house in Waverton, North Sydney, covered by an abstract self portrait, nearly 12 metres wide.

Eventually he came across a problem he couldn’t solve, and he succumbed to cancer in Sydney in 1997. He was 75.

I say the following in deep affection: He was a showoff, a braggart, a big noter… talking to Frank was like chatting to a pneumatic drill… but when he was hot, like those other vibrating Hungarians — he was amazing.

Max Robinson, 2006.