This text marked the induction of Douglas Annand into the AGDA Hall of Fame in 2000.

When kids of my age were growing up in graphic design in the late Fifties, early Sixties, there was only one master. This guy. There were others who were terrific. Mostly Sydneysiders. And we had our very own Dick Beck in Melbourne. But Douglas Annand stood out head and shoulders.

Before we were aware of the rigours of the Swiss School, before we all fell dangerously in love with Milton Glaser and Push Pin, before all the Michaels had minimalised the West Coast and David Carson was simply the worst nightmare of a comp carrying a tray of type – we had Doug Annand to marvel at.

I remember making pilgrimages to see the latest Annand appendage to handsome new buildings in Sydney. The rich, glowing, unbelievable concoctions of compressed junk, twisted glass, and fire infuriated metals, magically morphed into seamless murals, screens and hangings that seemed to evoke that sealife, crustacean-strewn, sun-filled, beachside Sydney look that also pops up in the work of Annand’s friend, Gordon Andrews, and certainly the painter, John Olsen.

Andrews says of Annand, ‘He was a natural. He had no need for overseas travel. He had no need of influences. He just did it. He always knew exactly what he wanted to do, and he just did it.’

A Queenslander, Annand originally wanted to be a jeweller. His father thought the Bank more appropriate. The Bank it was, but by 1925 he took a job offered by a printer who eventually encouraged him to study commercial art. After one term he set up as a freelance and was self taught from then on.

By 1930 he was in Sydney and his distinctive spidery line began to attract attention. He was much in demand by the big, fashionable department stores of the day – Farmers, David Jones, Grace Bros, Anthony Horderns, and he worked for them continuously.

In 1939 he was appointed principal designer for the Australian Exhibition at the New York World’s Fair. After that his reputation soared and he could pick and choose his clients. He designed other international exhibits for the government before the war intervened and he found himself in the RAAF as a camouflage artist with other leading designers, Geoff Collings, Alistair Morrison and Gordon Andrews.

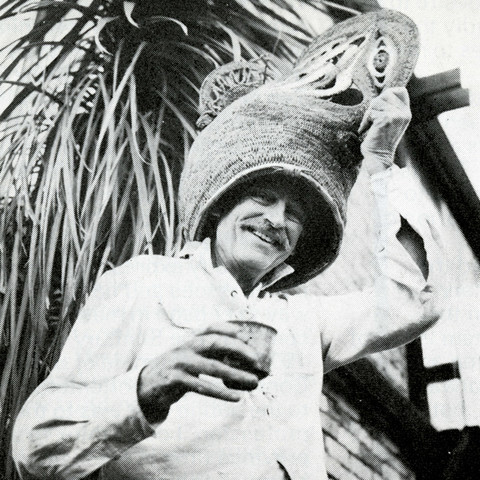

The year 1948 saw the beginning of a relationship with P&O which lasted many years. He designed posters, fabrics, brochures, menus, and many murals for luxury liners like the Orcades and the Oronsay. He was the master of so many mediums. His watercolours won prizes including the Mosman Art Prize. His murals twice won the Sulman. His covers for the literary magazine Meanjin became collectors items. His stamp designs also. ‘Nothing is wasted with me,’ he said in 1969, referring to his love of materials, and his esoteric collection of oddments and trinkets, destined to find repose in the glittering three dimensional designs he concentrated on after the Sixties.

In 1975 he took his last trip to Europe. And when he died in 1976 he was busy making a stained glass window for a local church. ‘Most who are familiar with his work agree that he was something of a genius’, says Geoffrey Caban in his book A Fine Line. Count me in.

Max Robinson, 2000.