This text marked the induction of David Lancashire into the AGDA Hall of Fame, 2014.

Australian graphic design owes a debt of gratitude to David Lancashire’s Aunty Maude. Recognising her nephew’s appreciation for drawing, she suggested the Circle Studio in Stockport just outside of Manchester as a suitable destination for the talented eleven year old. His mother Olive worked hard to earn the four shillings for each lesson, a prudent investment as it turned out.

Under the mentorship of the school’s founder John Henshall, he studied an intriguing mix of hand skills including watercolour, oil painting, lettering, heraldry and black and white illustration. He learnt the foundation stones of both fine art and commercial art, instilling ‘an appreciation for the tactile, texture and patina of life.’1

Leaving school at just sixteen, his first job included technical illustrations for Massey Ferguson tractor catalogues. Moving on after a month as a financial recession hit, he quickly found other work with Industrial Art Services, a studio with diverse clientele including American animation studio Hanna Barbera, Marks & Spencer and the Carborundum Company of America. Applying Zip-A-Tone to Yogi Bear books and drawing freehand ellipses on Bristol Board were typical of the disciplined tasks he undertook as a junior, technical skills he would apply throughout his career.

With three mates he headed off to Sydney in 1966, staying in Australia for three years. It was the beginning of a lasting love affair with the country. After working at Clarence Street Studios in ‘Vogue House’ (the building is no longer around) for a period of time, Lancashire left Sydney to settle in Melbourne. He found work in the most straightforward of manners, beginning with the letter ‘A’ in the Yellow Pages. Art Associates, a studio run by Brian McCartney, was his first phone call. By the end of the day he had a job.

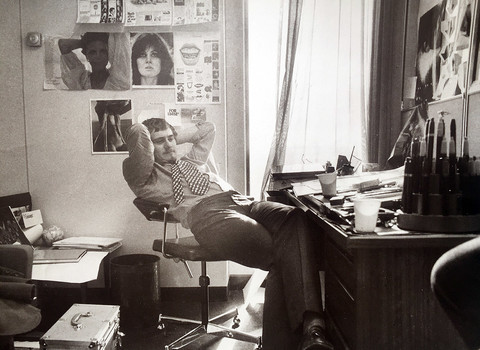

David left in 1970 for the UK but, homesick for the bush, he only stayed a year. Returning to Melbourne he met his wife Di, a darkroom person at the renowned photographic studio Brian Brandt and Associates. For a decade he honed his skills as an advertising art director but increasingly found himself doing less directing, and more art.

In 1976 he began freelancing. Designing and illustrating a series of children’s books called Practical Puffins was one of his first significant commissions. Published in 1977 and distributed internationally, the series was created to provide children with basic skills in everything from carpentry to gardening and bicycles. These imaginatively engaging books were a perfect platform for his unique skillset.

The onset of the rapacious 1980s saw Lancashire’s workload expanding rapidly, with commissions from publishing companies, educational institutions and clients within the rapidly expanding FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) sector, more familiarly known as packaging. Safeway supermarkets contracted the studio for all manner of pack and label designs ranging from ice confectionary to pizza boxes. Of particular note was a design for Safeway’s home brand milk, the first four colour printed carton in Australia. Featuring a charming rural scene with a hint of the Old Country, it was illustrated by Ron Brooks, now one of Australia’s best known children’s book illustrators, and studio finished artist and letterer Godfrey (Geoff) Fawcett. The latter worked with Lancashire for almost 20 years, and his contribution to the studio’s success cannot be underestimated. In 2011 their unique partnership was acknowledged in the form of a retrospective of the late Fawcett’s collected works, curated lovingly by Lancashire.

Along with Safeway home brand packaging, perhaps his highest profile work from this period was the logo and titles for the The Man from Snowy River, a movie which is still amongst Australia’s top ten grossing films. ‘I like to ensure that a successful design helps make a successful product’ Lancashire commented at the time. The studio also developed a significant following in the fashion sector, working with iconic labels JAG and Coogi, as well as designing all the advertising for Sportsgirl. ‘That account paid the studio wages for a decade,’ he has said.

The awards cabinet bulged. MADC (Melbourne Art Director’s Club) and AWARD (Australian Writers and Art Directors) Annuals from the period are peppered with its work, alongside other local giants of the time including Emery Vincent Associates, Flett Henderson & Arnold and Malpass & Burrows. David’s long commitment to industry-based activities has seen him serve as a judge on many such awards schemes, and he has been a Victorian President of AGDA and of the MADC. In 1996 he became a member of graphic design’s most exclusive club, AGI (Alliance Graphique Internationale), and he has worked with the Board of ICOGRADA (International Council of Graphic Design Association) on special projects relating to indigenous design.

By the end of the decade, Lancashire had accumulated 16 staff. The studio moved from its modest digs in Prahran Market to a bigger space in Newry Street Richmond. Illustration was central to his practice, and many of the country’s most acclaimed practitioners worked with David, either as freelancers or under his direct employment. The unique alchemy of this work is most evident in the numerous promotional pieces completed for printers, embellishers and paper merchants, targeting his fellow designers. These exquisitely crafted works were completed just as the digital revolution arrived, and design moved from the hand to the cursor.

The onset of desktop publishing in the 1990s must have been challenging for a designer so committed to his artisanal philosophies. Of computers he has said ‘they enable us to do wallpaper very quickly, and in 42 different colours.’2 A skilled teacher, he implores his students to ‘put marks on paper and draw,’ advocating chance and accident as key components of the creative process. He has also endorsed the notion of ‘slow design’ in contrast to the fast-food style of work so prevalent today, a bi-product of the digital paradigm.

In 1993, with the studio at the peak of its powers, he experienced an epiphany while working on the Bowali Visitor Centre in Kakadu National Park with architects Glen Murcutt and Troppo. Describing this critical juncture he said ‘working with Indigenous people gave me a precious insight into this country. It was life changing, and gave me a sense of place and an appreciation that helps me see Australia in ways that I don’t believe you can come to grips with in the city.’3 He says it was the late Gagudju Elder and poet, Bill Neidjie, who taught him ‘how to look and feel this country.’

These are long-term, deep and challenging engagements, as far removed from the comforts of a city studio as one can imagine. His trusted cohort for such interpretive work includes anthropologist and photographer wife Di, alongside interior designers, architects, landscape architects, biologists, archaeologists and, critically, traditional Aboriginal owners. Notable examples of this collaborative approach include the Bowali Visitor Centre and the Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Centre, both located on the Kakadu National Park, the Karrijini Visitor Centre in Western Australia and Bunjilaka at the Melbourne Museum.

David describes these projects as very ‘hands-on’, a comment perhaps best explained by this passage: ‘On one interpretive element, I burnt the sign, then took the marks up the wall and put crushed charcoal into the rammed earth floor. We were trying to convey the importance of fire in Kakadu.’4

Such experiences also galvanised his political and social convictions, inspiring posters and texts advocating an engagement with the cultural and environmental challenges faced by Australia and beyond. An exhibition in the late 2000s featured cards and posters designed to glow in the dark, a comment on the attempted rehabilitation of the former British Nuclear testing site at Maralinga.

In 1998 he sold his company to Grey Advertising and merged with Steve Blenheim Design to form Lancashire Blenheim Design, an ill-fated partnership which dissolved just months later. He returned the business to its former name, and moved the studio from South Yarra to Carlton North, an address he still occupies today. He continued to forge close relationships with architects and landscape architects. Numerous projects ensued including signage work for Werribee Zoo, Healesville Sanctuary, identity and packaging for The Royal Botanic Gardens and a memorable body of work with paper merchants KW Doggett.

In recent times he has focused solely on his art practice, continuing an enduring fascination with flora and fauna both here and abroad. A recent exhibition at South Melbourne’s Cyclone Gallery featured a mob of his beloved ‘roos’. The silhouetted collages, constructed by hand from his prodigious collection of ephemera, are strikingly powerful graphic forms. They are the latest, and certainly not the last, examples of David Lancashire’s five-decade journey traversing, exploring and blurring the line between art and design.

Dominic Hofstede, 2014.

-

David Lancashire, ‘The Blind Alphabet. (Think. Then draw round your think!),’ Open Manifesto #3 (2007). ↩

-

David Lancashire interviewed by Jenny Brown, ‘Drawing with a clear eye on design,’ The Melbourne Age (2005). ↩

-

David Lancashire interviewed by Heath Killen, ‘David Lancashire,’ Desktop Magazine #290 (2013): 56. ↩

-

David Lancashire interviewed by Heath Killen, ‘David Lancashire,’ Desktop Magazine #290 (2013): 58. ↩