Note: This text was first published in Desktop #277.

The venerable broadcaster, writer and film-maker Phillip Adams has described Alex Stitt as a ‘genius, the most under-recognised bloke in the country.’ Speaking at the launch of his longtime friend and colleague’s book Autobiographics, Adams metaphorically described him as a ‘Replicant,’ a reference to the genetically engineered beings of the seminal 1982 sci-fi classic, Bladerunner. For those unfamiliar with Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, Replicants are robots, identical to humans in appearance, but blessed with superior intelligence, strength and agility. Leafing through the pages of Alex Stitt’s 296 page magnum opus it is clear he is blessed with an otherworldly intellect. As to his strength and agility, my guess would be he is limber in mind more than body these days given his advanced years (he is 79).

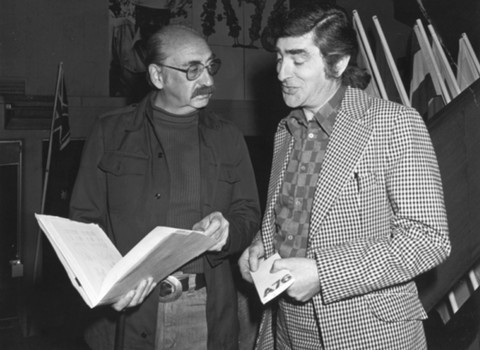

Adams also made the observation that Stitt’s work is ‘imbued with laughter’, and praised its lack of solemnity. He shares this irreverent trait with many of our country’s best designers, from the surrealist absurdity of Les Mason and Garry Emery to the nonconformist idiosyncrasies of Andrew Ashton. Humour has been a part of the Stitt visual arsenal from the moment he joined Channel Nine in 1959 as a twenty two year old to produce animated films and commercials. It was there that he met the exquisitely talented Bruce Weatherhead, and in 1963 they established Weatherhead and Stitt, a formidable partnership perfectly in tune with the visual zeitgeist of the 1960s.

Over a golden period of ten years they produced a startling array of work which climaxed in their most ambitious undertaking, the Jigsaw Factory. An article from a Melbourne newspaper at the time details the aims of the venture thus: ‘What is it? Designing things for children, which Weatherhead and Stitt intend to manufacture and market in a fun centre with built-in research and testing areas where children’s reactions can be assessed.’ Years ahead of its time, this paradise for children (and adult graphic designers) proved the financial and emotional undoing of the studio, and in 1974 the two went their separate ways.

Out of the wreckage Stitt formed Al et al, and quickly established a burgeoning business with advertising, corporate design, animation and film graphics at its core. One of the revelations of Autobiographics for me was the extensive body of graphics Stitt completed for the film industry. Fred Schepisi was working in advertising as Phillip Adams’ assistant when Stitt met him in the 1960s. The two would become lifelong friends and collaborators on countless projects including such well known films as The Devil’s Playground (1976), The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith (1978) and Six Degrees of Separation (1993). Most recently, Stitt completed the titles for Schepisi’s latest movie The Eye of the Storm, ‘all done at home on the Mac.’

Stitt may well be Australian graphic design’s most exposed individual. I mean this not in the literal sense, though he and Bruce Weatherhead were once photographed in their birthday suits for a client gift, their chests emblazoned with hand written typography long before Stefan Sagmeister made it his signature. Rather, I refer to the exposure his work has received over the years. Consider the dozens of extraordinary animated commercials he produced over a 22 year period for the Christian Television Association, reaching countless Australian households through their black and white, and then colour, television sets. Or his celebrated Life. Be In It. work which gained the unprecedented accolade of a Macquarie Dictionary listing for its famous anti-hero Norm, or reflect upon the number of cinema goers here and internationally who have seen his titles for Fred Schepisi’s Hollywood movies and mini-series.

In the often elitist world of design, labels such as accessible and approachable and are used pejoratively, as though being popular can only be obtained through compromise. This can surely not apply to Alex Stitt. His work displays what all great visual communication has at its core; an ability to connect with a defined audience. It’s just that his audience has been bigger than most of us mere human graphic designers can ever hope to reach.

Dominic Hofstede, 2011.