With so many new art movements coming and going – Neon Art, Pop Art, Op Art, kinetics, new-wave cinema – the old traditions once again seem to be under scrutiny. One of Australia’s best-known Op artists is Hungarian-born Frank Eidlitz, who recently left Australia on a Churchill Fellowship to study Visual Communications at Massachusetts Institute of Technology under world-renowned Professor Gyorgy Kepes, author of The Language of Vision.

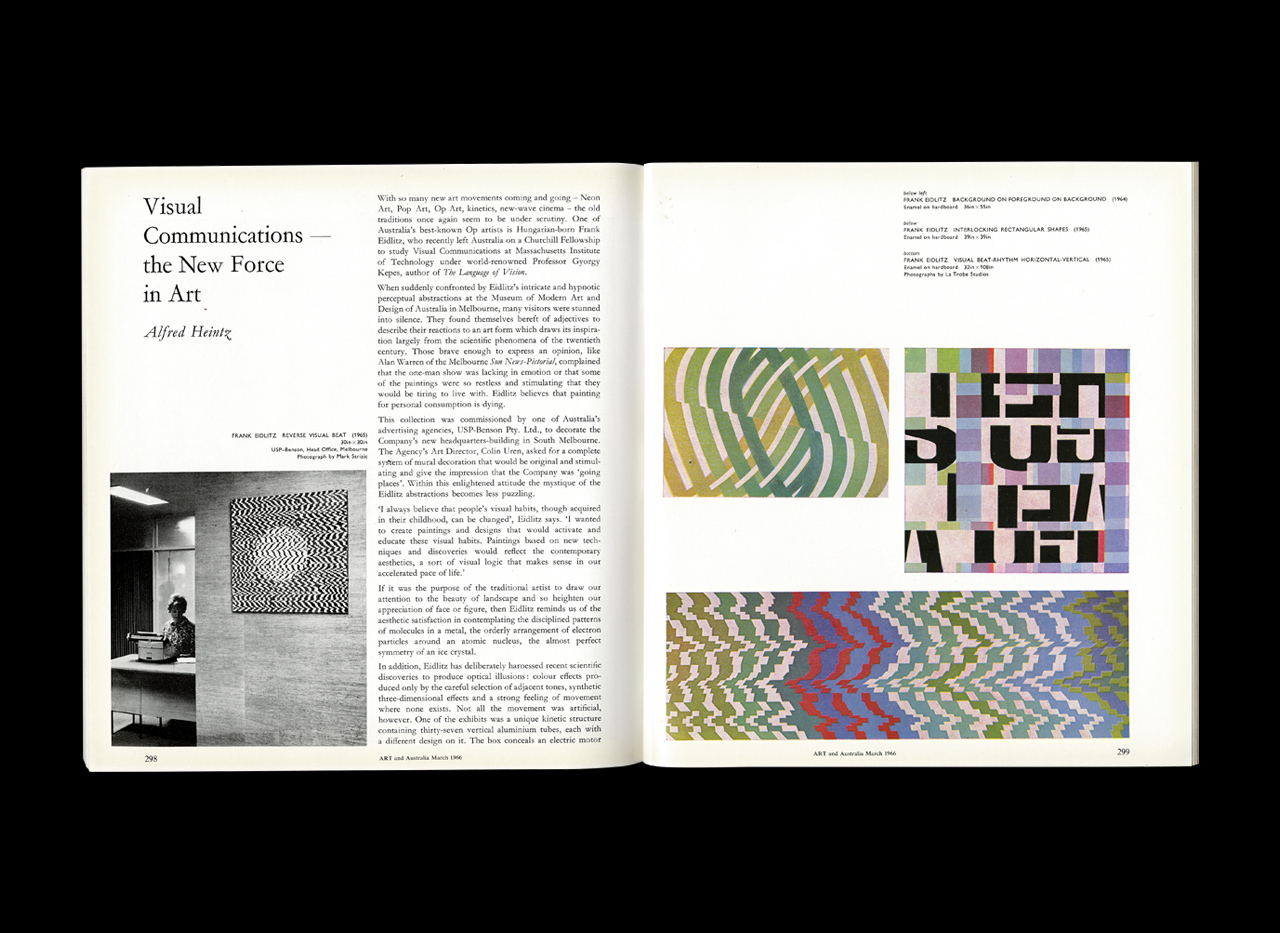

When suddenly confronted by Eidlitz’s intricate and hypnotic perceptual abstractions at the Museum of Modern Art and Design of Australia in Melbourne; many visitors were stunned into silence. They found themselves bereft of adjectives to describe their reactions to an art form which draws its inspiration largely from the scientific phenomena of the twentieth century. Those brave enough to express an opinion, like Alan Warren of the Melbourne Sun News-Pictorial, complained that the one-man show was lacking in emotion or that some of the paintings were so restless and stimulating that they would be tiring to live with. Eidlitz believes that painting for personal consumption is dying.

This collection was commissioned by one of Australia’s advertising agencies, USP Benson Pty. Ltd., to decorate the Company’s new headquarters-building in South Melbourne. The Agency’s Art Director, Colin Uren, asked for a complete system of mural decoration that would be original and stimulating and give the impression that the Company was ‘going places’. Within this enlightened attitude the mystique of the Eidlitz abstractions becomes less puzzling.

‘I always believe that people’s visual habits, though acquired in their childhood, can be changed’, Eidlitz says. ‘I wanted to create paintings and designs that would activate and educate these visual habits. Paintings based on new techniques and discoveries would reflect the contemporary aesthetics, a sort of visual logic that makes sense in our accelerated pace of life.’

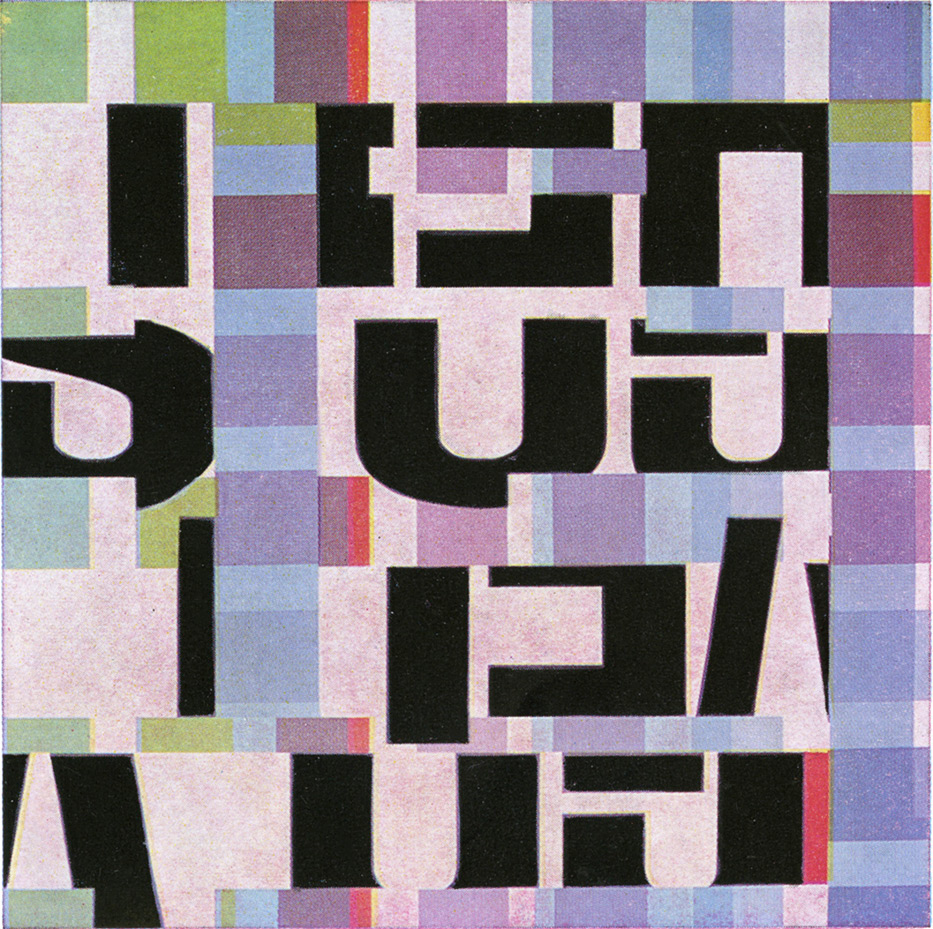

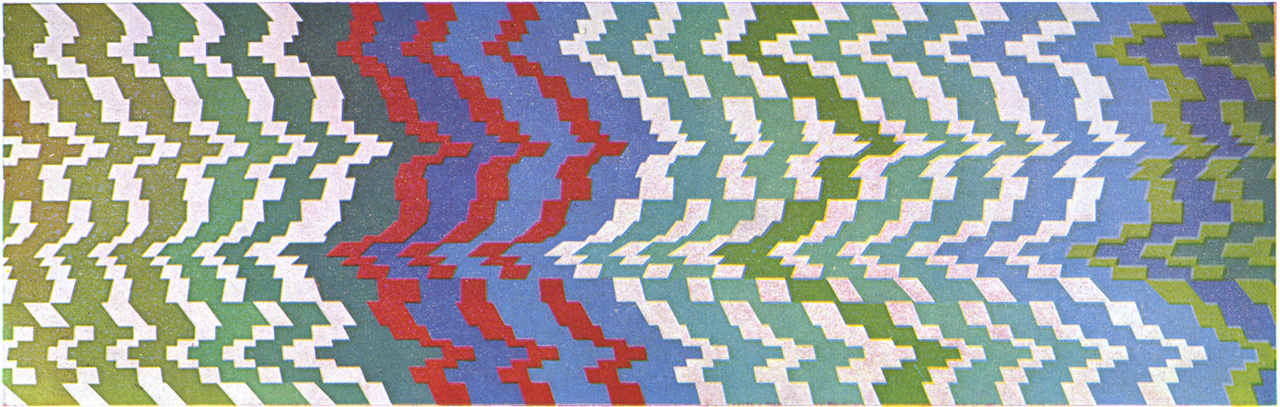

If it was the purpose of the traditional artist to draw our attention to the beauty of landscape and so heighten our appreciation of face or figure, then Eidlitz reminds us of the aesthetic satisfaction in contemplating the disciplined patterns of molecules in a metal, the orderly arrangement of electron particles around an atomic nucleus, the almost perfect symmetry of an ice crystal.

In addition, Eidlitz has deliberately harnessed recent scientific discoveries to produce optical illusions: colour effects produced only by the careful selection of adjacent tones, synthetic three-dimensional effects and a strong feeling of movement where none exists. Not all the movement was artificial, however. One of the exhibits was a unique kinetic structure containing thirty-seven vertical aluminium tubes, each with a different design on it. The box conceals an electric motor and an internal motion that can be programmed to produce limitless variations of colour and shapes. It aims, with the constantly changing movement, to create a variety of stimulating images in the spectator’s mind.

Yet another novelty of the exhibition was Eidlitz’s freedom in selection of materials. Just as the artist received most of his inspiration from the science and technology of the twentieth century, some of the exhibits actually were produced by science. The moire patterns for instance are produced when figures with periodic rulings are made to overlap; when lines intersect at a slight angle they produce ripples and curves not really inherent in the grid. Moiré patterns are also used in scientific experiments – studies of X-rays, acoustical and water waves, and in designing lenses, etc.

Far from being a lonely experimenter working only for his own satisfaction, Eidlitz is very conscious of the effect produced on the public. The shock was deliberately planned to make the viewers more aware of the current development in visual communications. ‘People wear blinkers all the time’, he says. ‘You must shock them so they look up.’

Photograph by Mark Strizic.

The slowness of the public to appreciate optical art is no mystery to Dr Ursula Hoff, Curator of Prints and Drawings, National Gallery of Victoria, who says ‘Symbolism must be part of an accepted tradition to get a real response to it. Without some kind of familiar signpost it is difficult for the viewer to appreciate what the artist is saying. With painting of this kind you have to be attuned to it and the majority of Australians will not be able to reach the right wave-length until the new symbolical language is more universally understood.’

‘What I’m basically concerned about in my paintings is structure, rhythm, harmony and form’, says Eidlitz. ‘By form, I mean a rigorous organisation and interplay of surfaces, lines and values. It’s in this organisation, alone, that my conception and emotion become communicable. I believe with Jung that in the subconscious mind there’s a vast reservoir of formal images and symbols that have universal meaning. How childish to expect artists to employ images which were the symbols of the past! But how can we expect the public to understand the basis of an abstract art without training? If we expect our businessman or industrialist to discriminate visually and intelligently, and to develop a contemporary taste of his own, visual-art train ing must become the basis of all education systems. Visual training as opposed to conceptual training so far has been neglected.

‘I am a visual artist’, he continues, ‘working with any medium that can best express what I want to say. The question that interests me is, “What role has art to play in our emerging technological and egalitarian society?” I say it should be an integral part of our educational programme in its widest sense.’