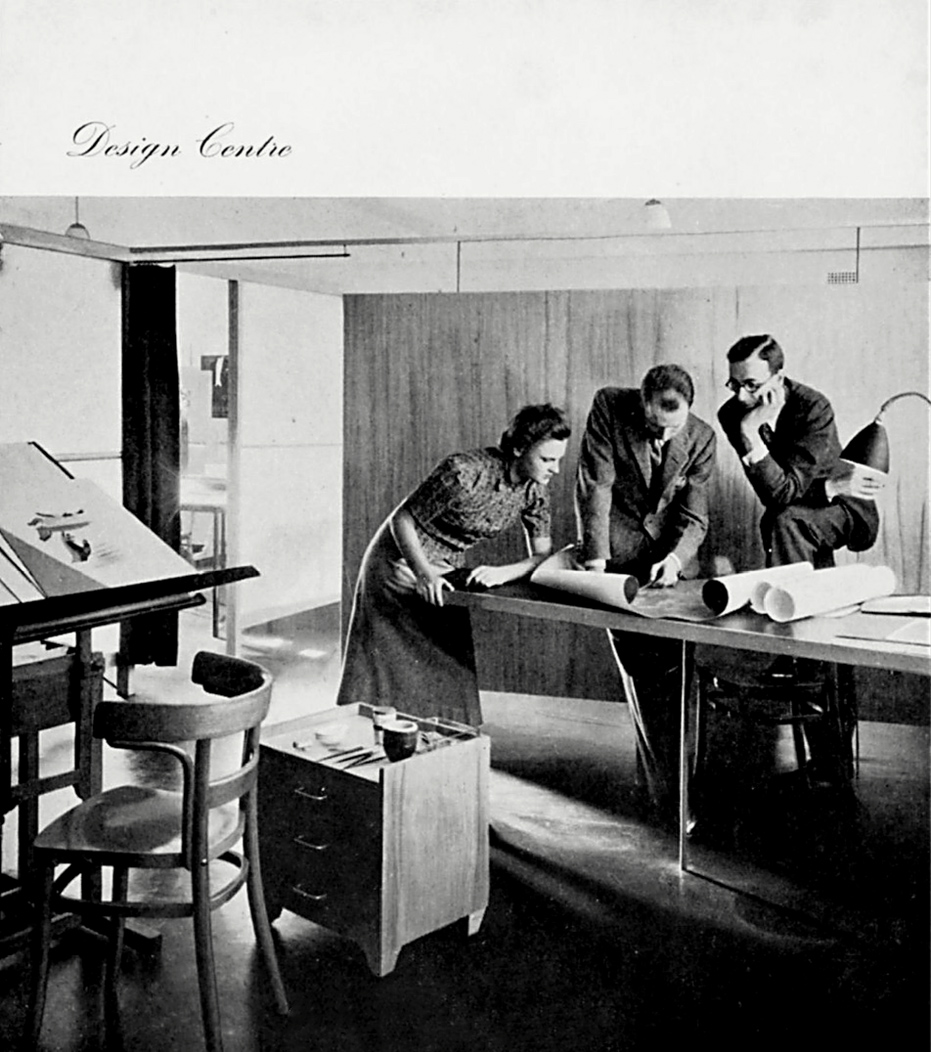

When Haughton James arrived in Australia in February 1939, he had an immediate impact on the emergent design industry. At first, Senior Creator Director of J Walter Thompson, he joined Dahl and Geoffrey Collings in setting up the Design Centre, Australia’s first professional design studio in 1939. The Design Centre was located in Federation House, Phillip Street, Sydney, which also housed the offices the arts publisher Sydney Ure Smith who, together with the department store magnate, Charles Lloyd Jones, was preparing to launch Australia National Journal, the focus of which was the practice of design within ‘Art, Architecture, Industry, Travel.’ The journal was a significant pre-war effort to promote the importance of design to the national agenda. The first issue featured an article by James, ‘The Designer in Industry: A Serious National Need’, which was ground breaking in its effort to theorise the importance of ‘industrial design’ as a modern professional practice within Australia’s economic, social and cultural production.1

Intended to be ‘a vehicle for all forms of expression in the Arts and Industry’, Australia National Journal marked a significant shift away from the association of modern design with fashion and society. With its focus on manufacturing, economic and cultural growth and the article by James, it wove the marriage of art and industry into the emerging wartime rhetoric of national responsibility, development and recovery. Experienced in publicity and advertising, James joined forces with Ure Smith and Lloyd Jones in promoting commercial art and industrial design as new creative industries that would enable Australian manufacturing to compete on the international market. Describing himself as a ‘high class huckster’, he brought a dynamic energy to the promotion of design, featuring prominently in the media, as he set about involving all sectors – commercial, industrial, political and cultural – in a public debate about the importance of ‘Good’ professional design to the national agenda.2

Photograph by Dahl and Geoffrey Collings.

Collection: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

Within modernist historiography, Haughton James’ speedy rise to prominence could be attributed to the aura of authenticity that accompanies the migration of a designer who experienced the real thing to the colonial margins. But James was not an unknown within Sydney’s contemporary art and design scene. Quite the contrary, before coming to Australia, James had made his mark as an Art Director and design publicist in London in the heady days of the 1930s when modern advertising and the concept of Art and Industry was coming into its own. This was the era of Edward Mc Knight Kauffer, of the Shell Posters, Underground and the LNER campaigns, when design was beginning to be professionalised and design societies established, and enlightened businessmen and cultural figures were joining with designers in promoting the new ideal of Art and Industry. Emergent modern designers were being praised for democratising art, with exhibitions of their ‘commercial art’ being held at leading London galleries, while writers such as Herbert Read, John Gloag, Arthur Bertram and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy amongst others, were beginning to theorise the principles and practices of modern ‘industrial’ design 3. At the grass roots level, a plethora of trade journals and publications including Commercial Art provided the how-to information and instructions for the everyday practice of modern design.

James, like many of his era, rejected the option of a university education to join the new creative industries, preferring instead to learn design on the job while attending art school at night. He began working in print workshops before moving into commercial art, freelancing and becoming an art director with the London branches of the American advertising agencies, Erwin Wasey and Co. and H K Mc Cann and Co. James appears to have been a natural entrepreneur, using his British private school education and cultured family background to great effect to position himself as a new styled, cultured businessman who was able to create crossovers between industry, business, advertising and the commercial arts. He established the London School of Advertising in 1927 and organised the first International exhibition of Modern Photography at the Wertheim Galleries, London in 1933. A council member of Society of Industrial Artists (1930), he drafted their Code of Fair Practice in 1935 and began promoting the need for design standards through media interviews, lectures and journalism 4. Within his writings, James expressed British reservations about modernism arguing in one that ‘contemporary’ design, ‘meaning designing for people living today’ was less misleading. Published in Art and Industry, Industrial Art, Advertising Monthly, his articles called for standards in packaging, graphics, advertising and lettering, and promoted emerging designers including the Australian couple, Dahl and Geoffrey Collings, who were making their mark in England.

Photograph by Dahl Collings.

Collection: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

James met the Collings at Wasey and Co, and was well known to the contingency of Australians working in London, including Alistair Morrison, Elaine Haxton and Gordon Andrews, and the architect, Syd Ancher, with whom he roomed 5. Geoffrey Collings was working for Wasey; Dahl and Alistair Morrison with Moholy Nagy on the Simpson Department Store, Piccadilly, the first holistic application of Bauhaus/Constructivist principles to a large-scale commercial project. The Collings’, in particular, were attracting critical acclaim for their documentary film work, and their joint exhibition with Morrison, Three Australians, at Lund Humphries Gallery, in June/July 1938.

James passage to Sydney followed the path of the Collings’ return home via Tahiti in late I938. He no doubt knew of Sydney’s thriving commercial art and advertising design scene that had been forming under the patronage of Ure Smith and Lloyd Jones. When he arrived in Australia, interest in modernist architecture and design was high, partly due to the return of artists and designers from working overseas. But the enthusiasm for the reforming potential of modern design had been growing throughout the 1930s, as part of the post depression recovery and this, together with expanding employment opportunities, had led to the formation of Australian Commercial and Industrial Artists Association, ACIAA, in Melbourne in mid 1939. With the spectre of WWII promising to cut Australian market dependency on Commonwealth imports, national leaders were turning their attention to manufacturing for the war effort and the home market and, with this, design as a new form of expertise. By late 1939, the consensus was that Design was going to be important to the war effort and recovery, and thus it was important to begin educating and debating standards in design and manufacturing, as Lady Dugan explained to the audience at the opening of the ACIAA’s first annual exhibition in June 1940.

With work plentiful, James took up a position at J Walter Thompson, and turned his attention to becoming a publicist for the emergent Australian design industry, drawing on his English experience to give credibility to his arguments. Joining with the Collings, he set up the Design Centre, Australia’s first, if somewhat short-lived, professional design studio, specialising in packaging, product design, photography, documentaries, modern publicity, advertising and art direction. Located close to Ure Smith’s offices, its opening was featured in the first edition of the Australia National Journal when published in late 1939. The Design Centre was significant in many ways, not the least of which was that it provided the model of practice for the new Design and Industries Association of Australia, DIAA, that Ure Smith, Lloyd Jones and James had been working to established with the patronage of influential figures, including the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, the newspaper baron Keith Murdoch, Ernst Fisk, Harold Clapp and Russell Grimwade.

Modelled on the British Design Council, the DIAA’s charter was ‘to improve the design of all things Australians live and use; and … promote closer cooperation between Australian designers and manufacturers to this end’ 6. Membership was open to all who wished to improve the quality of Australian life, and was intended to cover every branch of industry and provide a common meeting ground for manufacturers, distributors, designer, architects, educationalist and consumers. This was to be facilitated by comprehensive exhibitions of well-designed goods, the establishment of a National Register of Designers for the use of industry, meetings, lectures and an extensive public relations campaign run by James.7

Emergent designers were grouped in with trades such as lithographers, engineers or draftsmen and employed without codes of practice including basic award wages.

While ACIAA’s role as a large association was to unite and promote the interests of its members, the DIAA’s role was educate industry, politicians, and the public to an understanding of design expertise and the role of design in shaping the everyday. As James recalled in later life, when the ACIAA and DIAA were first established, freelance commercial and industrial artists had no labor code, no standing, and no ownership of their works, no copyright or basic wage. Emergent designers were grouped in with trades such as lithographers, engineers or draftsmen and employed without codes of practice including basic award wages. The struggle to achieve recognition and a reasonable status for designers was slow and the DIAA’s role was to lobby and educate industry, business and the public.8

With the patronage of leading figures such as Prime Minster Menzies, the DIAA caught the attention of the press. This was primarily due to promotional work of James that included strategically timed press releases and broadcasts on the ABC, Australia National Broadcaster. Titled ‘What Beats Me’, his weekly radio talks were designed to promote the art and industry theory of Good Design while at the same time explaining the nature of modern design expertise together with its economic and social benefits. Acutely aware of the establishment’s distrust of modern artists he took care to use the success of the British art and industry movement to encourage industry leaders to believe that they too they could develop products that could compete on the world market.9

He also was careful to present a temperate picture of the modern designer, who he stressed, was ‘nothing like the designer of his father’s day. He does not call himself an “artist” – since his object is to produce solutions to real problems in terms of design, not to gild a pill by superfluous decoration.’ A ‘new artist’, who abhorred artistic licence, he concentrated instead on the production of ‘useful art’. Importantly, designers like the Collings and fellow members of the DIAA, were the product of an emergent international network of practice. While they had learnt a great deal ‘from the rough and tumble of technical training in art schools and studios, engraving plants and advertising agencies, big retail stories and display forms’, their international experiences and network of contacts distinguished them as ‘the designers of our world.’ 10

A unifying theme of Haughton’s campaigning was the differentiation of the modern designer from the artist/craftsperson/tradesman and this was the focus of his Australia National Journal article, ‘The Designer in Industry: A Serious National Need’. Drawing attention to the establishment of the British Council for Art and Industry, he used the article to pen a Good Design manifesto that called for the education of professionally trained designers. Good Design, he explained, was that which went beyond mere utility. It embraced the totality of the thing made, permeated its whole structure, met its necessities and made it work. More importantly, it met the human and spiritual needs of ordinary men and women through its creation of contemporary living. Outlining the history of industrialisation and the Bauhaus, he explained, the need for specialist design education as opposed to art education. He also drew attention to American manufacturers, who were tapping into the market power of design by employing consultants such as Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy and Gustav Jenson, and whose good-looking products were beginning to flood the Australian market. Without a supporting infrastructure of design and research, Australian industries, with their frontier make-do mentality, he argued, were under serious threat, because the ‘goods produced to meet the dire necessities of the pioneer’ would not stand up to modern competitive standards. What Australia needed was design standards, principles and trained designers together with educated factory workers and consumers. It was time for change, time for ‘the bearded artist’ favoured by elitist fine art galleries to be replaced by the modern designer whose role it was ‘to demonstrate that good design is for ordinary people in the ordinary things in their own homes’.11

The publication of Australia National Journal coincided with the onset of war, and this brought a premature end to the Design Centre and the DIAA, as James and his contemporaries were swept up in the war effort. James joined the AIF, and worked in camouflage before moving into propaganda, where he assisted the government’s advertising for war effort, producing poster campaigns for war bonds, and publications for the Australian Army Education department on the role of art and design in shaping the everyday.12 Discharged from the defence forces in 1945, James settled in Melbourne, establishing the industrial design firm, Haughton James Services in 1946 and employing Max Forbes and Arthur Leydin. He joined forces with Fred Ward, Peter Hutchinson, Victor Greenhalgh, Alan Warren, Max Forbes, Ron Rosenfeldt, Frances Burke, Gordon Andrews and Grant Featherston amongst others, and once again began campaigning for the professionalization of design, beginning with the establishment of the Society of Designers for Industry, SDI, in 1948. In late 1949 he played a pivotal role in designing and organizing, the ‘Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’, Red Cross Modern Home Exhibition in Melbourne, ensuring that it was an promotional showcase for SDI and the idea of an independent, design profession dedicated to the shaping everyday Australian life. In 1952 joined John Briggs in establishing Briggs and James, Australia’s first really solid advertising agency.

Denise Whitehouse

-

Richard Haughton James, ‘The Designer in Industry: A Serious National Need’, Australia National Journal, no.1 Winter, 1939, pp.87-91. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James quoted from his unpublished autobiography by Ray Marginson, Jimmy James: A Personal Memoir, Memorial address delivered at the Second Asia/Pacific Design Conference, Australia 1989, Mildura, August 26–29, p. 7, R H James Archives, Powerhouse Museum. ↩

-

Ashley Haviden, Advertising and the Artist, The Studio Publications, London, 1956. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James, Second Thought: The Autobiography of Jimmy Haughton James, unpublished typescript, c.1981, R H James Archives, Powerhouse Museum. ↩

-

Marginson, Jimmy James, p.10. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James, ‘Australian Designs Ignored: Artist’s Criticism: New Association’, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 1940. ↩

-

‘Australian Design and Industries Association’, Draft charter, Douglas Annand, Design Archives, Powerhouse Museum. The extensive press coverage included: ‘Improving Design in Industry: Australian Organisation’, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 December, 1939; ‘Linking Design and Industry: New Association Formed in Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 January 1940; ‘Australian Designs Ignored: Artist’s Criticism: New Association’, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 1940. The latter notes a meeting was held at which Mr Sydney Ure Smith presided was held and a constitution was adopted. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James interview with Richard Haese, Melbourne, undated transcript, R H James Archives, Powerhouse. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James, ‘Design in Industry: Australian Organisation’, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 December 1939. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James, Catalogue introduction, Dahl and Geoffrey Colllings, David Jones Galleries, Sydney, June 1939. ↩

-

James, The Designer in Industry. ↩

-

Richard Haughton James, Art, Everyday Day, Discussion Pamphlet, Army Education Service, no.17. ↩

This essay was sourced from The Design History Australia Research Network [DHARN].