Gareth Powell, a controversial Welsh-born publisher, arrived in Australia in 1967 to ‘a modicum of unfavourable publicity in the Australian press’ 1. His scandalous reputation resulted largely from the publishing of Fanny Hill by Mayflower Books in 1963. The bawdy 1748 novel is considered the first original English prose pornography, and, as publisher, the ensuing kerfuffle landed Powell in jail for gross indecency. Publicity surrounding the incident and resultant high profile court case helped change staid British laws relating to sexual content. Powell was cast as a provocateur, a role he would come to embrace throughout his career.

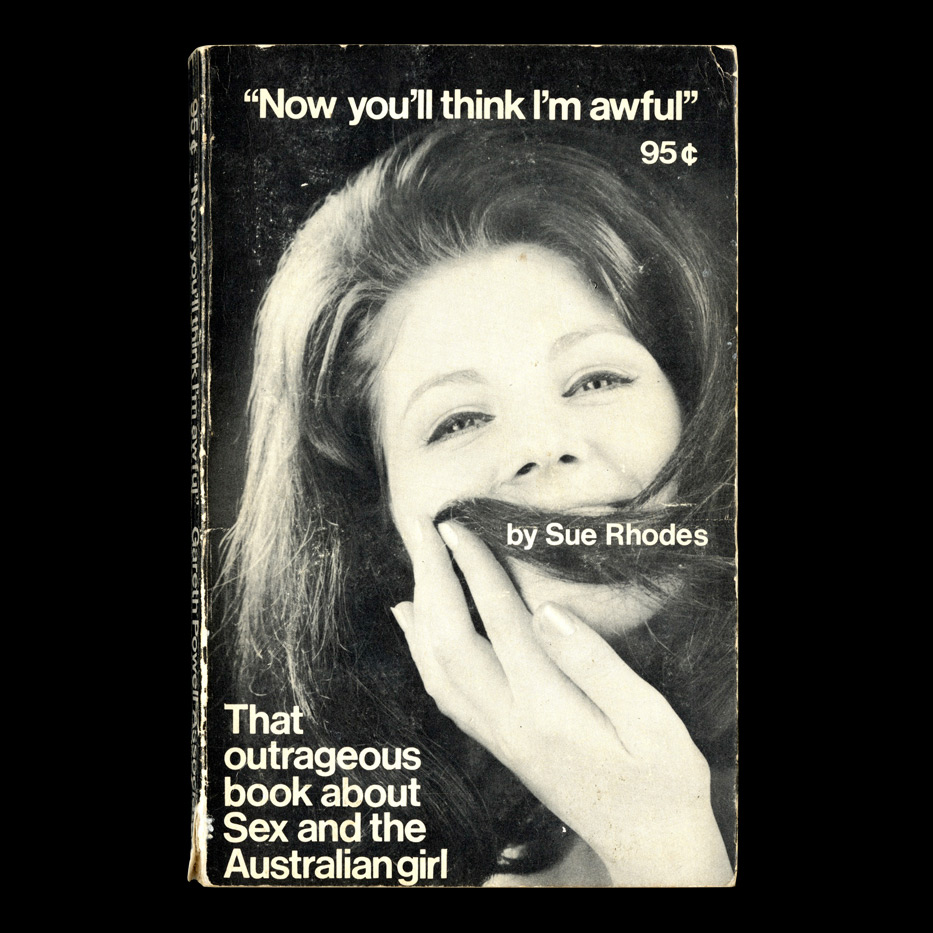

Powell was just 37 when he emigrated to Sydney, confident his larrikin persona would be better appreciated in his adopted country. Having established a new publishing venture under the name ‘Gareth Powell and Associates’, his first title was a raging success. Now you’ll think I’m awful was subtitled ‘That Outrageous Book about Sex and the Australian Girl’. A frank exposé by journalist Sue Rhodes, the book was a bestseller for Powell’s new imprint.

Shifting his focus to magazines, he initiated a number of new titles including Surf, which was aimed at the growing youth market, and (in association with Jack de Lissa) Chance. Inspired by Penthouse and Playboy and deliberately provocative, Chance soon became mired in court battles, most famously in a landmark case when issues were seized by Australian customs on arrival from Powell’s Hong Kong printers. The publisher recalled having the idea for his next magazine whilst sitting in court awaiting a verdict. ‘I had the idea for doing a women’s magazine as Chance was knocked on the head by a judge. I knew the kind of magazine I wanted’. 2

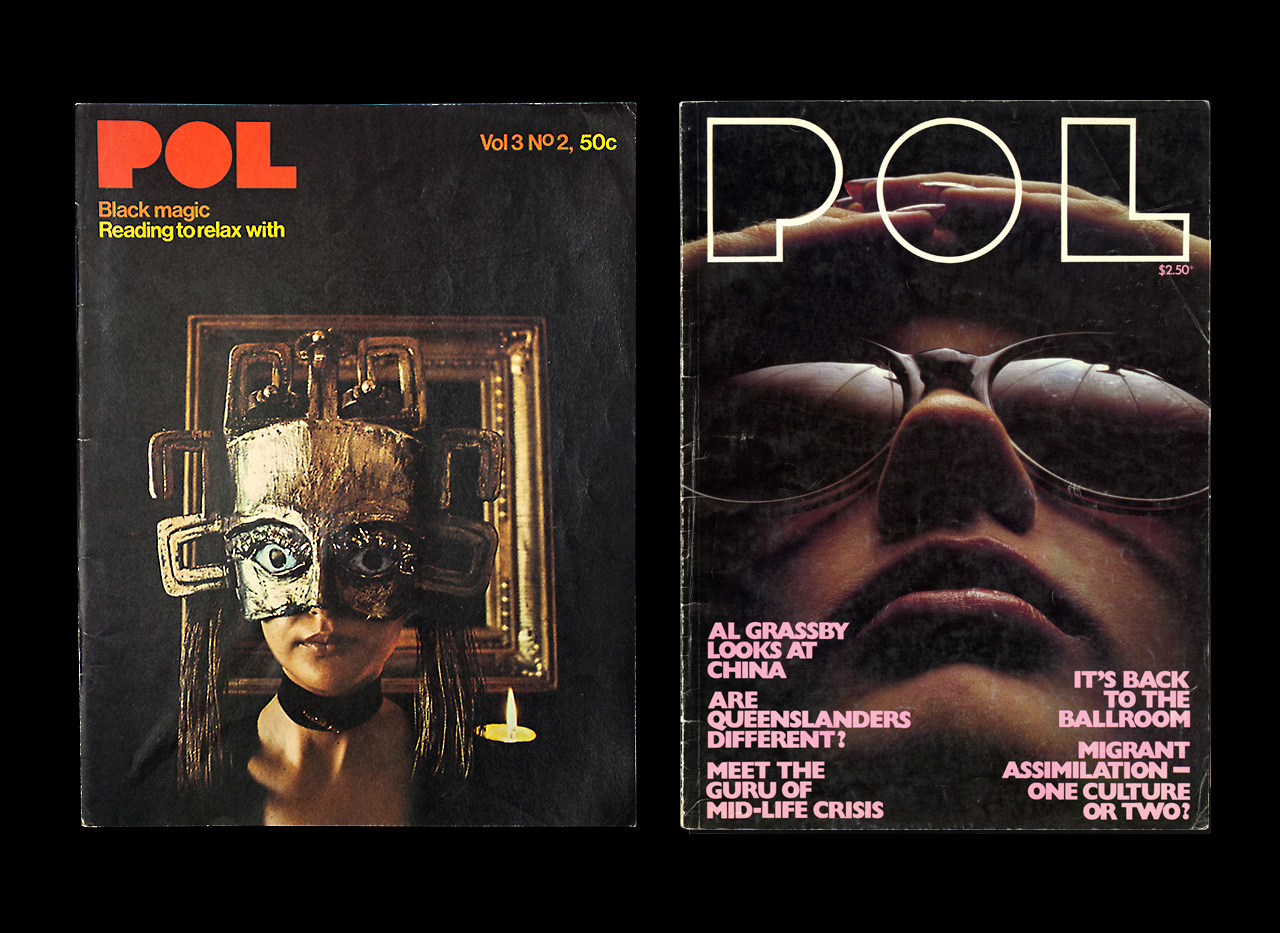

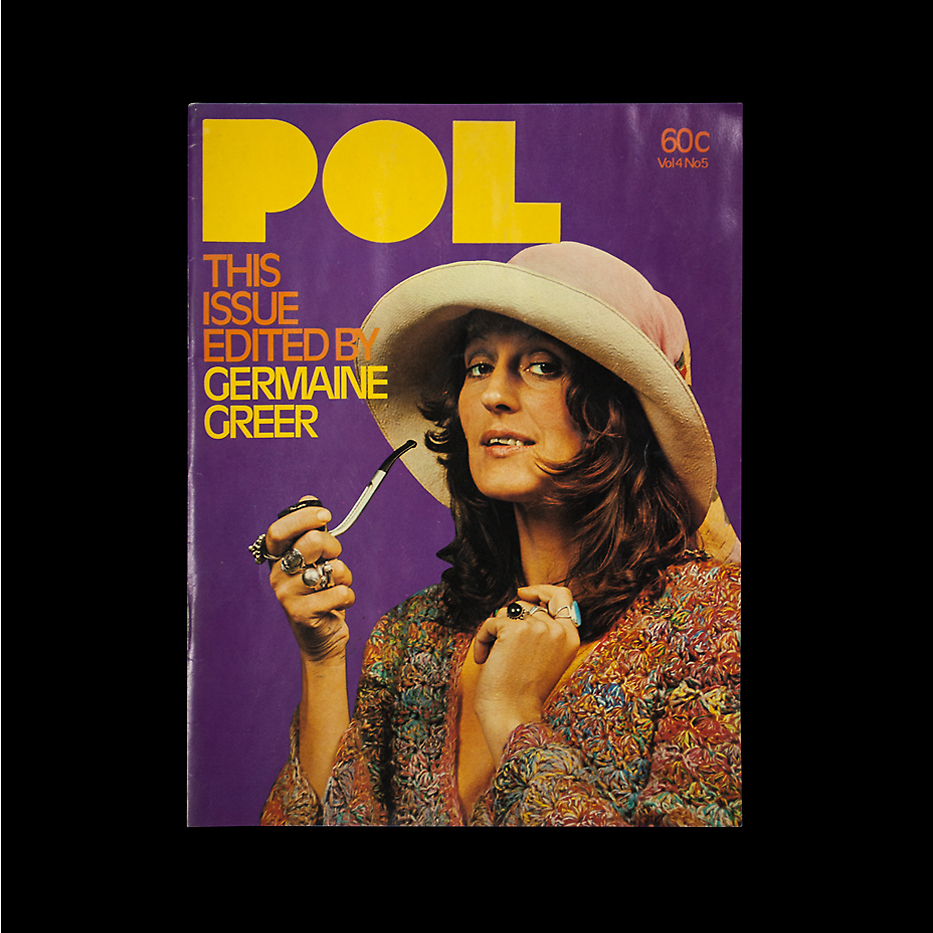

POL was an attempt to capture the radical spirit of the 1960s, packaged in a sophisticated, original format. Shocked at the poor standard of local printing, Powell created a benchmark magazine with high quality production values and an emphasis on bold editorial design. POL was the first major Australian women’s magazine to use colour offset printing, and the first to have its issues printed overseas; this was done by the Hong Kong branch of Dai Nippon Printing before issues were air-freighted to Australia. ‘We ditched hot lead typesetting from the beginning … the headings in those days were all Letraset. But I was totally shocked at what was accepted in Australia. Rubbish printing on rubbish paper’. 3

A pivotal initial decision was the appointment POL’s first editor. Based on a recommendation from Jack De Lissa, he approached Richard Walsh, a kindred spirit with his own controversial background as one of OZ magazine’s founders. 4 Walsh proved an astute choice, and contributed significantly to the new magazine’s success. The combination of Powell’s entrepreneurial flair and Walsh’s publishing instincts proved fertile. Of Walsh, Powell said ‘Clearly he was an editorial genius. With Richard you merely lit the touch paper and stood well back’. 5

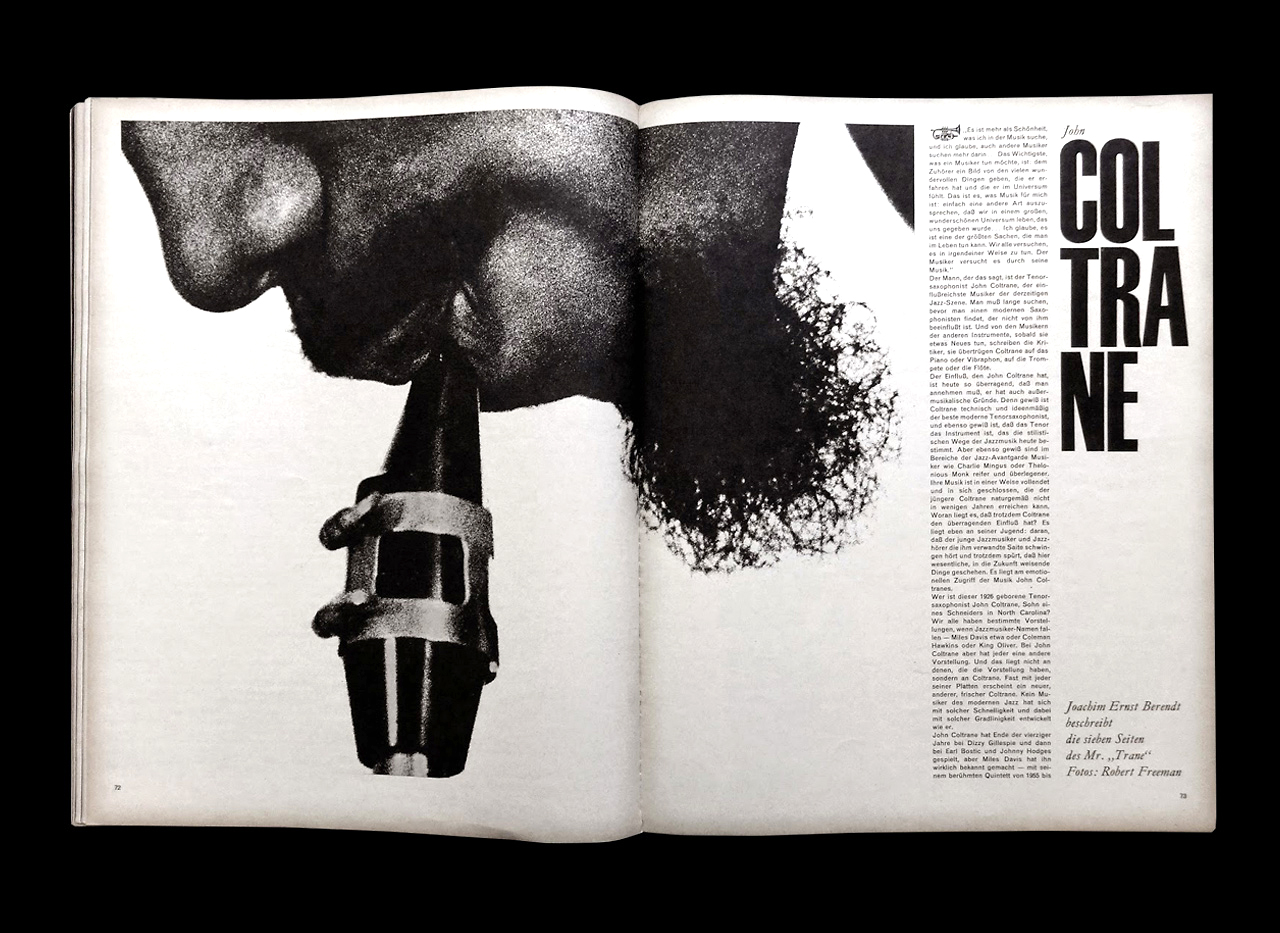

Powell also recognised that developing a distinctive editorial visual identity would be essential. In Graeme (Gus) Cohen he found an art director inspired by TWEN and NOVA, two of the most important magazines of the 20th Century. TWEN (1959–1970) was a men’s magazine with a bold aesthetic honed by the legendary German art director Willy Fleckhaus (Max Bill was the magazine’s inaugural art director). Fleckhaus pioneered a simple approach where large, impactful photography was juxtaposed with blocks of typographic content. The effect was visually dramatic, and TWEN’s editorial vocabulary was mimicked by countless admiring art directors. As TWEN’s notoriety grew, so did Fleckhaus’s power, and he effectively became the magazine’s second editor. He would occasionally invite visiting colleagues to assume his role while on holiday, including the London-based photographer and designer Harry Peccinnoti. 6

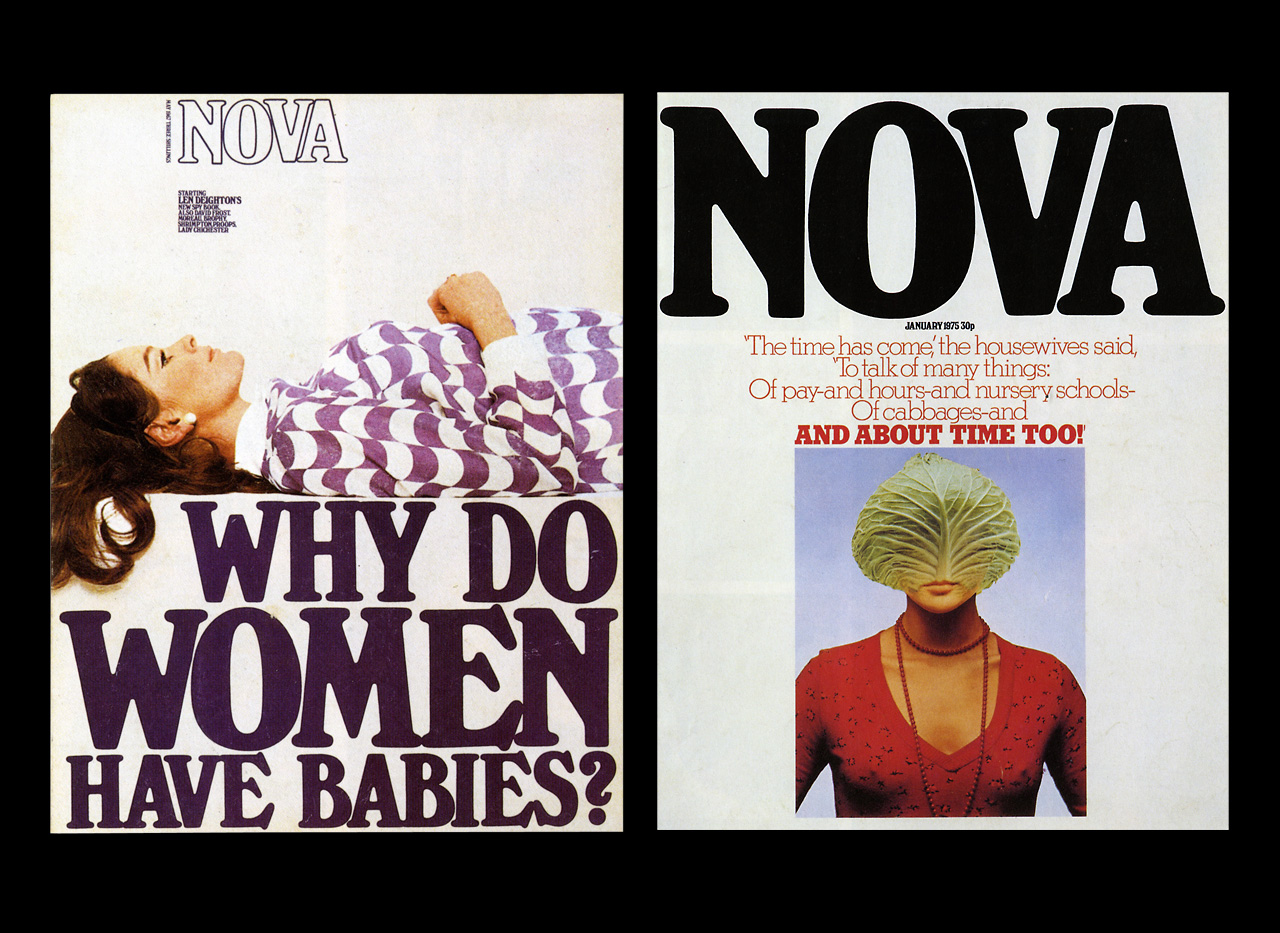

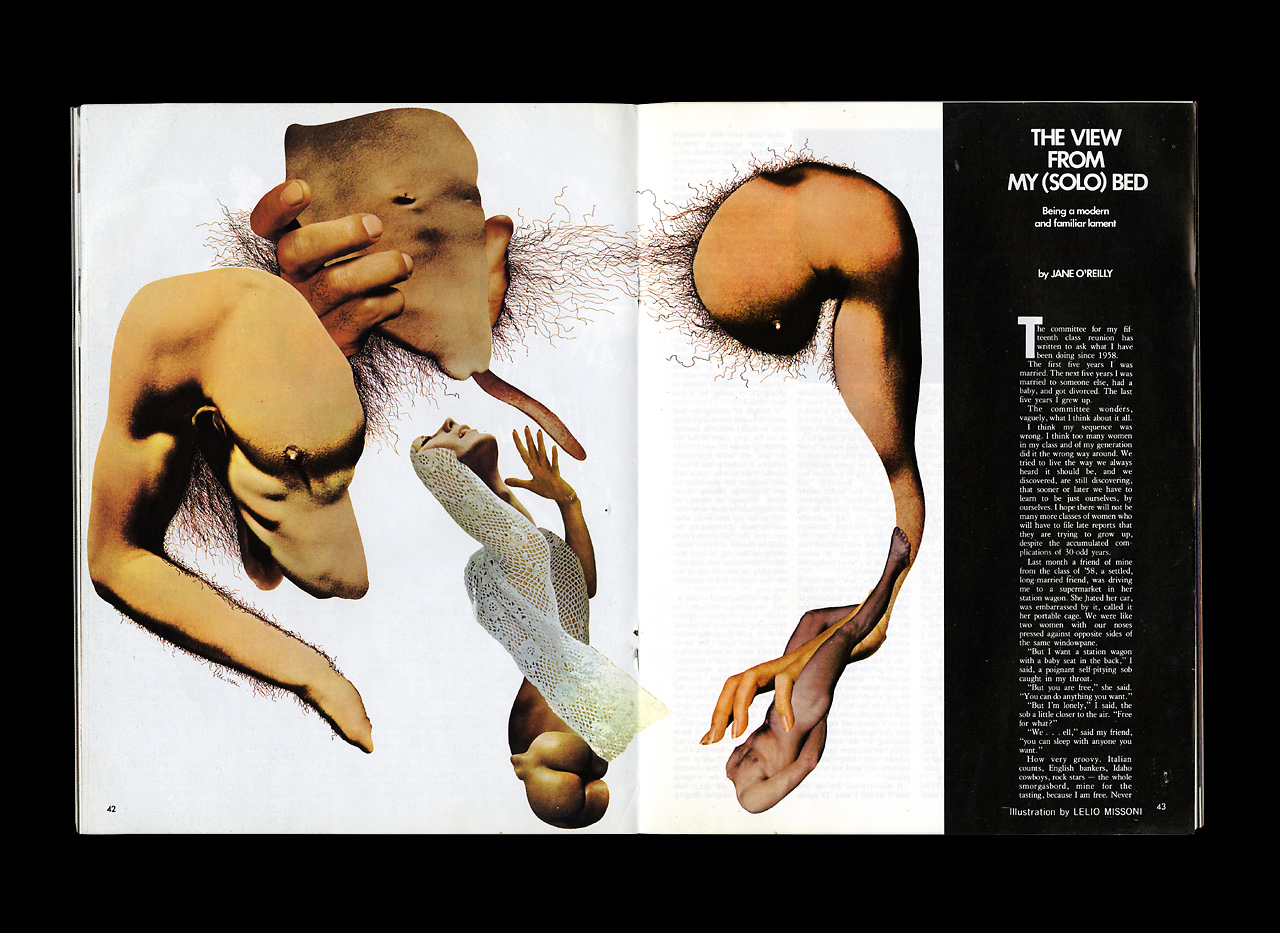

British magazine NOVA (1965–75) was created as a revolutionary women’s journal, ‘the new kind of magazine for a new kind of woman’. Like TWEN, it relied on ground-breaking editorial design, driven initially by Peccinnoti and then from 1969–1975, David Hillman. NOVA captured the spirit of London’s ‘Swinging Sixties,’ embodying a time of unrivalled creativity and sexual and artistic revolution. Reflecting upon the early issues of POL, the impact of NOVA is palpable, a reference point Cohen is happy to admit to: ‘We were very aware of NOVA, and were influenced by what it did’.

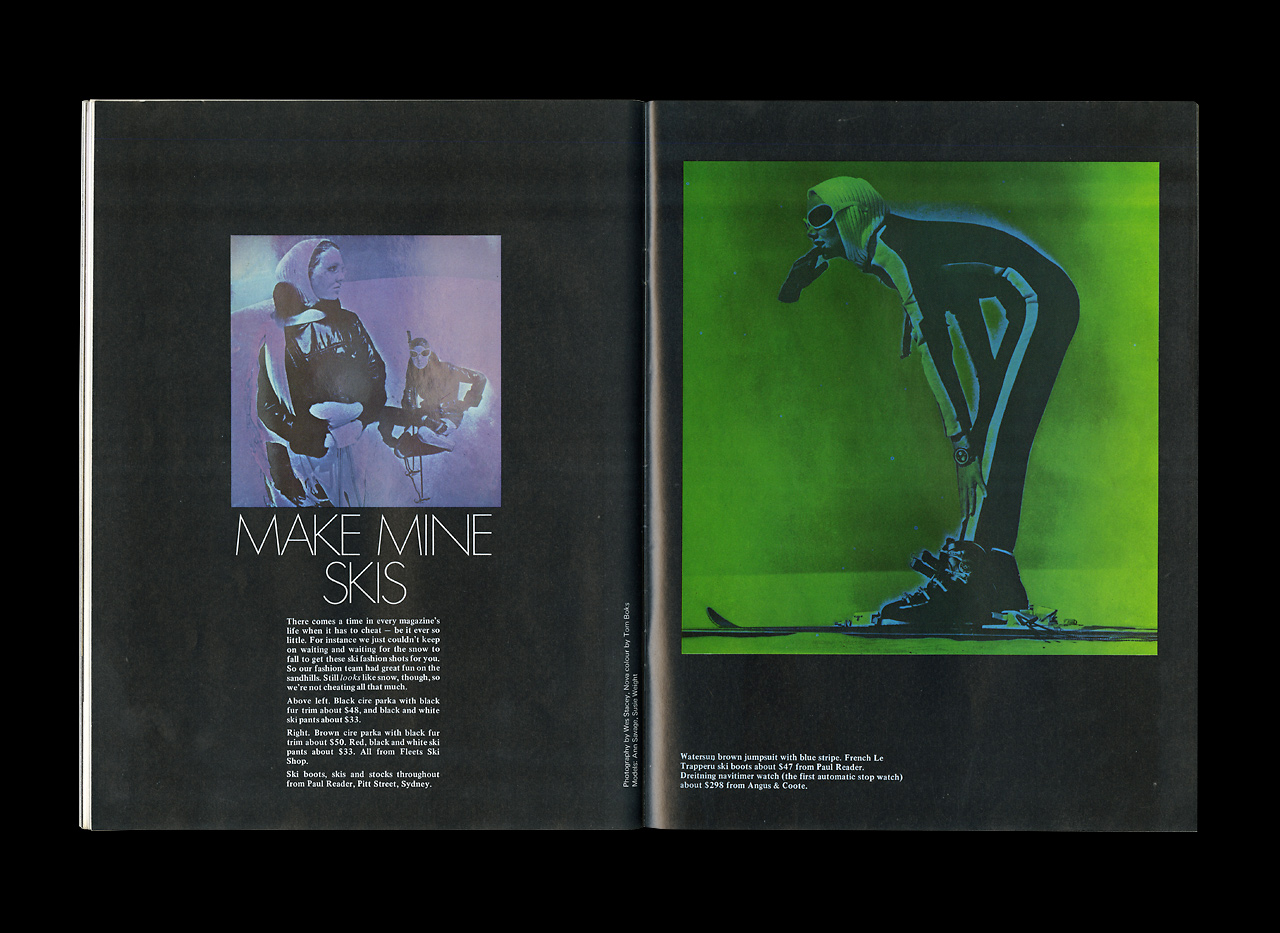

The pages of TWEN and NOVA featured the work of many great lensmen (and women). In Australia, as the sixties came to a close, a new wave of young photographers were seeking a platform to show their wares. Over time, Grant Medford, Graham McCarter, Wesley Stacey, Anthony Crowell, Douglas Holleley, Colin Beard, Lewis Morley, Greg Weight, Greg Barrett, Jacqueline Mitelman, Robin Stacey, Brett Hilder, Dieter Muller and Rennie Ellis all appeared on POL’s pages.

A lack of resources and tight budgets left much to the photographer’s initiative, but the open briefs provided almost total creative freedom. The resultant images were often experimental and progressive, and POL’s body of work, particularly within the field of fashion photography, is perhaps its most telling creative legacy.

With Gough Whitlam and his Labour Party on the rise in the early 70s, POL’s heady mix of edgy fashion photography, informative and challenging features and high production values aligned perfectly with the shifting sands of Australian culture. A roster of guest editors included some of the era’s most influential cultural figures including Germaine Greer (1972), Richard Neville (1974) and Don Dustan (1980).

Though Powell sold off his interests in POL in the early 1970s, the magazine continued until 1986. By the 1980s the women’s magazine market was overflowing with competitors, many heavily influenced by POL’s ground-breaking approach. Regular appearances in award annuals from this era indicate the level of respect POL retained from the design industry.

Powell’s charismatic energy drove the success of the imprint during the heady early days, and issues from that time reflect Australia’s emerging confidence in a period of extraordinary political and social change. The magazine’s aspirational disposition is evident in this quote from Don Dustan: ‘Pol delights in excellence, individuality, creativity and zest for life. We chronicle Australia’s maturity. We pursue the causes of the good. Australians of the world unite and read POL – you have nothing to lose but your cultural cringe’.7

-

“We know you’re awful.” Last modified April 26, 2015. http://www.sorgai.com/we-know-youre-awful/ ↩

-

POL. Portrait of a Generation. (Canberra, National Portrait Gallery, 2003), p7. ↩

-

Ibid, p.4. ↩

-

Richard Walsh was one of the founders of OZ, alongside Richard Neville and Martin Sharp. He edited the Australian version of the satirical magazine between 1963–69 while Neville and Sharp were in London. The UK OZ became the subject of well publicised obscenity trial in 1971, seven years after a similar case in Australia. ↩

-

POL. Portrait of a Generation. (Canberra, National Portrait Gallery, 2003), p.9. ↩

-

David Gibbs, NOVA 1965–1975. (London, Pavilion Books, 1993), p.29. ↩

-

POL. Portrait of a Generation. (Canberra, National Portrait Gallery, 2003), p.2. ↩